| Citation: | Fengshan LI, Jiandong WU, James HARRIS, James BURNHAM. 2012: Number and distribution of cranes wintering at Poyang Lake, China during 2011-2012. Avian Research, 3(3): 180-190. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2012.0027 |

Poyang Lake is a very important wintering place for cranes in China and East Asia. Two crane surveys were conducted at Poyang Lake during the 2011/2012 winter, the first on 18-19 December 2011 and the second on 18-19 February 2012. The survey covered the entire Poyang Lake basin, as well as two main lakes in Jiujiang (Saicheng Hu and Chi Hu), i.e., a total of 85 sub-lakes were surveyed. Both surveys recorded four species of cranes. The first survey on 18-19 December 2011 recorded 4577 Siberian Cranes (Grus leucogeranus), mostly in Bang Hu, Sha Hu and Dahu Chi, 302 Hooded Cranes (G. monacha), 885 White-naped Cranes (G. vipio) and 8408 Eurasian Cranes (G. grus), for the most part in the center of the lake basin. The second survey on 18-19 February 2012 recorded 3335 Siberian Cranes (mostly in Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve (PLNR) and its surrounding areas), 110 Hooded Cranes (largely in PLNR and its surrounding areas), 283 White-naped Cranes (86% in Bang Hu) and 2205 Eurasian Cranes (particularly in Duchang and Nanjishan NNR). The number of Siberian Cranes enumerated in December was 1000 more than the second count in February 2012. It is not possible to rule out double counting due to the close proximity of the main sites of the Siberian Cranes. During winters from 1998 to 2009, the average of the highest counts each winter was 3091, ranging from 2345 in 1996 to 4004 in 2002. By comparison with counts taken at other times, we therefore estimate a wintering population of Siberian Cranes of~3800-4000 at Poyang Lake. Additional evidence will be needed to raise the world population estimate. Our more recent surveys indicate a continuing decline in the number of White-naped Cranes and an increase in Eurasian Cranes.

Poyang is the largest freshwater lake in China and globally famous for its birdlife. The rich food resources provided by emergent and submerged aquatic plant diversity of this wetland is a major reason that hundreds of thousands of migratory birds travel to Poyang every winter. While winter counts vary from year to year, on average more than 400000 waterbirds make Poyang their winter home. Thus Poyang is by far the most important wintering area for waterbirds in East Asia and supports many rare and threatened species (Ji et al., 2007; Qian et al., 2009). For example, over 98% of the world population of Critically Endangered Siberian Cranes (Grus leucogeranus) and over 90% of the globally occurring Oriental Storks (Ciconia boyciana), also an endangered species according to the IUCN Redlist, winter at Poyang (Liu et al., 2011). Half of the world's vulnerable Swan Geese (Anser cygnoides) winter here. In two years of winter waterfowl surveys in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River Basin, Poyang Lake supported 12–15 species with more than 1% of regional waterbird populations (Barter et al., 2004, 2005).

Poyang Lake is a very important wintering place for cranes in China and East Asia. Besides Siberian Cranes, almost all of China's wintering White-naped Cranes (Grus vipio), one-third of China's Hooded Cranes (G. monacha) (Barter et al., 2004, 2005) and perhaps half of China's Eurasian Cranes (G. grus) spend the winter at Poyang Lake.

It is important to conduct counts of species on a regular basis at Poyang Lake in order to obtain accurate estimates of populations and understand trends for these species over time (Callahan, 1984; Nichols and Williams, 2006). Four crane species regularly winter at Poyang. These are large, charismatic waterbirds and the focus of national and international conservation efforts. These efforts include long-term ecological monitoring at Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve (PLNR) and coordinated basin-wide counts performed roughly every two years (Qian et al., 2009; Li et al., 2011). The last basin-wide count of cranes at Poyang Lake occurred in early 2009. Since then, there has been a major flood across Poyang Lake in the summer of 2010. The flood altered vegetation communities in many parts of the lake basin which, in turn, affected the foraging habitats and distribution of the Siberian Cranes and other waterbirds. The International Crane Foundation (ICF) and the Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve conducted two surveys in the winter of 2011/2012. The objectives of the surveys were: 1) to determine the number of cranes wintering at Poyang Lake, 2) to determine the locations of these waterbirds, and 3) to compare the number and locations of Siberian Cranes between this winter and previous winter surveys.

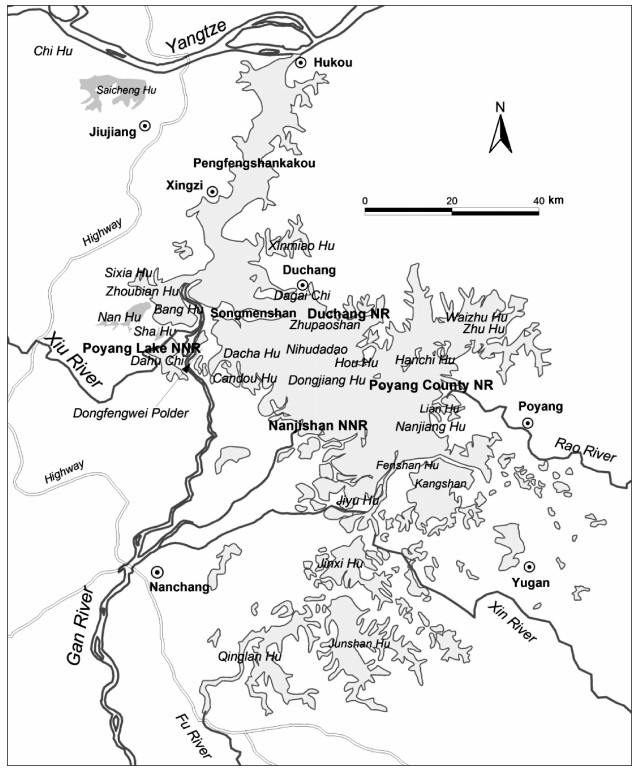

Poyang Lake (28°11′–29°51′N, 115°49′–116°46′E) is located in the southern part of the Yangtze River Basin and northern part of Jiangxi Province. The average width of the lake from east to west is 16.9 km, with the narrowest width of 2.8 km at Pingfengkakou where the lake water enters the Yangtze River. There are five major tributaries that drain the 162000 km2 watershed and the single outlet of the lake empties into the Yangtze River (Liu and Ye, 2000; Shankman et al., 2009).

Poyang Lake is a unique system that becomes a lake during the wet season and is a complex patchwork of river channels, isolated sub-lakes, mudflats and seasonally wet meadows during the dry season (Fig. 1). Poyang Lake has the shape of a bottle gourd and can be divided into two parts at Songmenshan. Its northern part is very narrow, basically a river channel to the Yangtze River, while the southern part is wide. The lake basin inclines from southeast to northwest and the lake bottom is very flat. Its water level and water volume change dramatically between the dry and rainy seasons. The highest water level of 22.58 m a.s.l. (Wu Song Elevation System) at the Hukou Hydrology Station was recorded on 2 August 1998, when the lake surface was 4066 km2 (Liu and Ye, 2000). Since 1990, the average lake surface area has been 2110 km2 in spring, 3900 km2 in summer, 3450 km2 in fall and 1290 km2 in winter (Huang, 2000). The dramatic fluctuation in water levels between wet and dry seasons creates a wide range of habitats for cranes, waterbirds and other wildlife over the entire lake basin. Due to its un-obstructed connection to the Yangtze River and its vast floodplain, Poyang Lake plays an important role in flood storage, water resource cycling and biodiversity conservation.

Poyang Lake has a humid subtropical monsoon climate, with hot summers, cold and humid winters, abundant rainfall and sunlight. The average annual temperature is 16–18℃ and the sum of annual temperatures ≥10℃ is 5515℃. There are 255–282 frost-free days per year. Annual precipitation varies greatly from year to year from 1340–1780 mm, with 46% falling from April to June. Annual evaporation is 800–1200 mm, mostly from July to September, resulting in flooding in the summer and drought in the fall. The long-term average water temperature is 18℃, with the highest water temperature of 29.9℃ in August and the lowest of 5.9℃ in January (Zhu and Zhang, 1997).

The entire Poyang Lake basin and its adjacent areas, such as Saicheng Hu and Chi Hu, were covered by the two surveys. More than 80 sub-lakes were surveyed. The basin survey was done within one day and Saicheng Hu and Chi Hu, far from the main lake basin, were surveyed the next day. The survey was conducted twice, once on 18–19 December 2011 and the second time on 18–19 February 2012. The first survey was conducted in mid-winter, when the crane population was stable and most likely to move within the Poyang Lake basin, while the second survey occurred approximately at the start of migration.

The survey involved 21 teams. Each team, equipped with a pair of binoculars (8 × 45) and a spotting scope (× 20–45), consisted of 2–3 persons, with 1–2 person(s) observing and the other recording. Binoculars were used to scan an area first to obtain a general understanding of the cranes in the area, while a spotting scope was used to identify and count the cranes.

All four species of cranes ― Siberian, White-naped, Hooded and Eurasian ― were recorded in each survey. A total of 14172 cranes were recorded in the December survey (Table 1), while the number of cranes was much lower in the February survey.

| Species | 18–19 December 2011 | 18–19 February 2012 |

| Siberian Crane | 4577 | 3335 |

| White-naped Crane | 885 | 283 |

| Hooded Crane | 302 | 110 |

| Eurasian Crane | 8408 | 2205 |

| Total | 14172 | 5933 |

The 4577 cranes recorded in the December survey were seen in 13 sub-lakes, of which 4225 were recorded in Bang Hu and Dahu Chi, accounting for 92% of the total count (Fig. 2). A third large flock of 136 birds was recorded at Hou Hu of Duchang. Most Siberian Cranes, recorded in the February survey, were also seen in PLNR and its surrounding areas. In Bang Hu 2296 cranes were recorded and in its adjacent lake, Zhoubian Hu, 690. These two lakes accounted for 89% of the total Siberian Cranes recorded in February. Dahu Chi and Hou Hu of Duchang had relatively low or no counts at all of Siberian Cranes in this survey, compared to the counts of 1657 Siberian Cranes in Dahu Chi and 136 in Hou Hu in December 2011.

White-naped Cranes were record in six sub-lakes at Poyang Lake on 18–19 December 2011. Among these six sub-lakes, 788 White-naped Cranes were found in Bang Hu, accounting for 89% of the total count (Fig. 3). Dahu Chi and Zhupaoshan had 50 and 30 birds respectively. In the February survey, the number of White-naped Cranes was less than in the December survey, with flocks present in only in four sub-lakes, with the largest flock of 242 in Bang Hu. Three other sites each had less than 20 birds. Dahu Chi and Zhupaoshan counted 50 and 30 respectively in December 2011, but in February no White-naped Cranes were recorded.

The Hooded Cranes recorded in December were mainly at Bang Hu (145 birds), Nanjishan Reserve (73 birds) and Dongjiang Hu (39 birds) (Fig. 4). In February, all Hooded Cranes were recorded at PLNR and its surrounding areas, with the largest flock of 55 recorded at Nan Hu, west of Sha Hu.

The December survey recorded the highest count of Eurasian Cranes ever at Poyang Lake. The top three sites with counts over 400 birds were all in Duchang ― Zhupaoshan, Nihudadao and Dagai Chi. In Zhupaoshan alone there were 5657 Eurasian Cranes (Fig. 5). Other lakes with over 100 birds were Fenshan Hu, Jiyu Hu, Hanchi Hu and Waizhu Hu. A total of 2205 Eurasian Cranes were recorded on 18–19 February 2012, much lower than the count in December 2011 of 8408. The largest flock of 650 Eurasian Cranes was found in the Zhupaoshan area, a similar location as in December 2011. In Nanjishan there were four flocks of Eurasian Cranes, each over 100 birds.

Securing good and reliable counts of waterbirds, even large waterbirds such as cranes, has always been a challenge at Poyang Lake with its large area, complex topography and unfavorable weather conditions (often foggy during winter). An aerial survey is a good approach for surveying large waterbirds, although foggy conditions, air traffic control and high costs have often prevented using this method. Ground surveys avoid these problems but, due to the large area, are more prone to double counting and even with many teams, take considerable time.

For our winter surveys, December had significantly higher counts than February. We are of the opinion that cranes are more concentrated and stable in December than in February, when it is almost time to begin migration. Median arrival dates have been 3 November for the Siberian Crane, 28 October for the White-naped and Hooded Cranes and 23 October for the Eurasian Crane, while the median departure dates have been 13 March for the Siberian and White-naped Cranes, 28 March for the Hooded Crane and 18 March for the Eurasian Crane, based on observations in the PLNR from winters 2002–2009 (Liu et al, 2011). For our February count, it is also possible that some cranes might have gone to other areas of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, such as Shengjin Hu. Of the four crane species, the Siberian and White-naped Cranes spend the winter almost exclusively within Poyang Lake, while the Hooded and Eurasian Cranes are often seen in other areas of the Yangtze River system (Barter et al., 2004). It should also be pointed out that our surveys did not cover all areas farther afield and in the drier parts of the lake or sub-lakes. For example, rice paddies were not counted systematically, but Eurasian and Hooded Cranes use wet rice paddies for foraging during typical winters, while Siberian Cranes almost never do and White-naped Cranes do so rarely (personal observations).

The number of 4577 Siberian Cranes recorded in December 2011 was the highest count ever at Poyang Lake. Of these Siberian Cranes, 4225 were recorded in Bang Hu and Dahu Chi; these two sub-lakes are only 4 km apart. PLNR staff re-checked the totals for these two locations in the afternoon of the same day and confirmed our enumeration. All the same, double counting cannot be ruled out since cranes often move between these lakes, while the timing of the counts was not tightly synchronized. None of the other winter enumerations of Siberian Cranes at Poyang Lake has recorded over 4100 birds in the past (see Table 2). On 11 March 2012 at 17:20, a total of 3400 Siberian Cranes were recorded at the north end of Dahu Chi, with independent counts of 3500 from the northern shore of the Xiu River looking into the same area at the same time, lending further support to the idea that large numbers of Siberian Cranes were consistently using areas around Bang Hu and Dahu Chi throughout the winter of 2011–2012 (J. Burnham, pers. observation). This enumeration was higher than our February count, suggesting that we probably missed a large number of Siberian Cranes during the February survey. The highest count for the species away from Poyang Lake came from Momoge National Nature Reserve in northeastern China, when over 3400 were present at one time (H. Jiang, unpublished data). During winters from 1998 to 2009, the average of the highest counts each winter was 3091 ― ranging from 2345 in 1996 to 4004 in early 2003 (Li et al., 2005, 2011). We therefore estimate a wintering population of Siberian Cranes of ~3800–4000 at Poyang Lake. Additional evidence will be needed to raise the world population estimate.

| Winter | Survey dates | Siberian Crane | White-naped Crane | Air/ground survey | Source of data |

| 1980/81 | Unknown | ~100 a | – b | Ground | Zhou and Ding (1982) |

| 1981/82 | Unknown | 91 a | – | Ground | Zhou and Ding (1982) |

| Unknown | 140 | – | Aerial | Zhou and Ding (1982) | |

| 1996/97 | Jan–Mar 1997 | 2345 | 2470 | Aerial | Ji et al. (2002) |

| 1998/99 | 11–12 Dec 1998 | 2004 | 870 | Aerial | Li et al. (2005) |

| 7 Jan 1999 | 2536 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) | |

| 16–17 March 1999 | 932 | 630 | Aerial | Li et al. (2005) | |

| 1999/00 | 11–15 Nov 1999 | 3643 | 3209 | Ground | Liu and Jia (2000) |

| 26–27 Feb 2000 | 897 | 1035 | Aerial | Li et al. (2005) | |

| 2000/01 | 9–14 Feb 2001 | 3008 | 4354 | Aerial | Ji et al. (2002) |

| Feb 2001 | 2087 | 2943 | Ground | Ji et al. (2002) | |

| 8 Jan 2001 | 1791 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) | |

| 2001/02 | 9 Jan 2002 | 3404 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) |

| 2002/03 | 9 Jan 2003 | 4004 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) |

| 2003/04 | Late Jan–early Feb 2004 | 2746 | 2713 | Ground | Barter et al. (2004) |

| 2004/05 | 14–28 Feb 2005 | 2683 | 1491 | Ground | Barter et al. (2005) |

| 2005/06 | – | 3131 | 1568 | Aerial | Li et al. (2011) |

| 2006/07 | 15–23 Dec 2006 | 2715 | 1757 | Ground | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 2008/09 | Feb 2009 | 3003 | 1017 | Aerial | Li et al. (2011) |

| 2011/12 | 18–19 Dec 2011 | 4577 | 885 | Ground | This study |

| 19–19 Feb 2012 | 3335 | 283 | Ground | This study | |

| a only covered the western part of the lake basin; b no data. | |||||

The 8408 Eurasian Cranes recorded represent the highest count at any time at Poyang Lake. The number of Eurasian Cranes at Poyang Lake has been increasing over the past 15 years, while it appears that this species is now more widely distributed across China during winters than in the past. There were seven counts at PLNR during winters from 1996 to 2006; the average of the highest winter counts was 721, ranging from 180 in 1999 to 1361 in 2006 (Wu and Ji, 2002; Li et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011). The increase of the Eurasian Crane population wintering in China might be due to its success in breeding and its expansion into agricultural areas. In Europe, the number of Eurasian Cranes has increased considerably. This species relies on agricultural lands for foraging on its breeding grounds and along their flyways (Prange, 2012).

The highest count for White-naped Cranes in our survey was 885, although counts of this species at Poyang during other parts of the winter returned higher numbers. On 09 February 2012 at 13:44, J. Burnham observed over 1500 White-naped Cranes loosely scattered across the large mudflats along the northeastern portion of Bang Hu (observation location: 29°14.68′N, 115°58.21′E). On 06 March, 2012 at 14:30, over 1000 White-naped Cranes were observed where the drainage from Zhoubian Hu enters into Bang Hu (observation location: 29°13.96′N, 115°55.70′E), with most of the observed birds foraging in the sedge/forb zone immediately adjacent to the waters edge. The enumeration of this species at Poyang Lake has been declining over the past 15 years and warrants further efforts to monitor this species closely in order to confirm the extent and reasons for this decline. There were 14 counts during winters from 1996 to 2012 (see Table 2); the average of eight counts from 1996 to 2004 was 2278, while the average for the six counts from 2005 to 2012 was 1167 (Ji et al., 2002; Barter et al., 2004, 2005; Qian et al., 2009; Li et al., 2011). There is no evidence that significant numbers of this species are now wintering elsewhere in southern China. Droughts in their breeding areas in recent years in Mongolia and northern China and the consequent failure of breeding success of the cranes (Goroshko, 2012; Yan et al., 2012) may have been the main cause for the decline of its wintering population at Poyang Lake.

Most cranes were observed and recorded in areas of the PLNR, Duchang, Nanjishan and in Poyang County (with the Eurasian Cranes more widely distributed), while there were no cranes recorded in areas north of Duchang. The main sites in these four areas have been designated as national or provincial nature reserves. Based on experience from this and other surveys in recent years, the PLNR and Nanjishan National Nature Reserve have a relatively good capacity for monitering waterbirds. Duchang Nature Reserve (provincial) has good infrastructure and competent staff and has been doing extraordinarily well in waterbird monitoring and protection. Mainly due to a lack of regular and sufficient funding from the government, this reserve has been struggling to keep up with its mandate, a condition which applies to almost all provincial nature reserves. Poyang County Nature Reserve (provincial) has no infrastructure or personnel and is very limited in its ability to monitor or protect waterbirds.

There were several sub-lakes/sites with consistently high counts of cranes during our survey as well as in previous surveys, such as those at Bang Hu (PLNR), Dahu Chi (PLNR), Sha Hu (PLNR), Hou Hu (Duchang), Zhupaoshan (Duchang), Dongjiang Hu (Nanjishan), Dagai Chi (Duchang) and Zhu Hu (Poyang).

Cranes are susceptible to a variety of habitat changes. Following the summer flood of 1998, a large number of Siberian Cranes stayed in Sixia Hu before December 1998. This lake was not affected by the flood due to the large dyke that separates it from the rest of the Poyang Basin, while it is likely that the submerged aquatic plants, on which the birds depend, were not adversely affected to the same extent as similar plants were in other portions of the lake basin (see Cui et al., 2000). After 2000, people started raising crabs in the lake, which correlated dramatically with a significant reduction in sampled aquatic vegetation (Burnham and Barzen, 2007) and increased human activity at the lake, with a corresponding decrease in its use by the Siberian Crane (Li et al., 2005). Aquaculture and the resultant human activity is likely a contributing factor as to why Siberian Cranes were not observed at Sixia Hu following the flood of 2010, even though the dyke at the lake again mitigated the direct impact of floodwaters on the sub-lake. Candou Hu, a sub-lake located in the southeastern part of Dacha Hu, had Siberian Cranes foraging in relatively high numbers throughout the 2007/08 winter as well as during the previous winter, with a maximum count of 2100 birds (Li and Burnham, 2008). Over the past three years, however, no cranes have been seen at Candou Hu. This pattern again correlates with the presence of crab farming at the lake.

The Siberian Crane is a species that relies heavily on shallow water and wet mud. The number of foraging birds is highly correlated with areas with a high density of Vallisneria spp. tubers that are within accessible water depth (Meine and Archibald, 1996; Burnham, 2007). However, during our previous aerial survey on 26–28 February 2000, 46 Siberian Cranes were sighted on the rice paddies at the Dongfengwei polder (Li et al., 2011). Harris (2000) reported 26 Siberian Cranes foraging on rice paddies in the same area a week later on 7 March. Dykes of the Dongfengwei polder were breached by the 1998 flood, while farming has not been allowed in the polder since then. The rice stubble in the field in the polder was from the 1998 spring planting, but the location lacked aquatic plants such as Vallisneria or Potamogeton spp.

In the summer of 2010, high water levels persisted for a long period at Poyang Lake. Both the water level and the duration of the high water period were unusual events for the 56-year record of water levels in the basin. By January 2011, many Siberian Cranes, along with Tundra Swans (Cygnus columbianus) and Swan Geese, began feeding in upland sites of the sedge/grass zone, which continued in February and March at Poyang Lake (Barzen et al., 2011; Huang, 2011). Switching diets from foraging on aquatic macrophyte tubers to agriculture fields has been studied in Tundra Swans wintering in Europe (Nolet et al., 2002), although habitat switching by these species has not been documented before at Poyang. Habitat switching by Siberian Cranes in the winter of 2010–2011 did not appear to have a detrimental effect on the ability of individual birds to migrate to staging areas in northeastern China in the spring of 2011 (H. Jiang, personal communication), but longer-term impacts on the breeding patterns of these birds are unclear. Recent work on Whooping Cranes (Grus americana) in North America has shown a strong link between poor foraging conditions on wintering grounds and a subsequent drop in breeding output by this species (Gil de Weir, 2006), a pattern that is likely similar to that of the Siberian Crane. Further attention needs to be paid to the nutritional value of sedge/forb species compared to aquatic macrophytes as well as whether habitat switching by birds represents a sustainable foraging option with minimal long-term effects on the breeding patterns of this species.

Although it is difficult to obtain good counts on the number of cranes at Poyang Lake, it becomes crucial to maintain winter counts on a regular basis to determine long-term trends of crane populations. Equally important, survey methods ― such as timing, routes and survey personnel ― should be consistent, so that results from different years can be comparable.

The decline of the White-naped Crane population needs more careful study. While we continue to monitor the number of White-naped Cranes wintering at Poyang Lake, their movements and habitat use/selection need to be determined, in order to improve our understanding of their habitat use and availability along with their interaction with other crane species, other waterbirds, as well as with the human communities of Poyang. In addition, it is essential to initiate collaboration on research and monitoring of this species between the wintering and breeding grounds to determine threats in both areas and to help development and implementation of conservation plans for this species.

Siberian Cranes forage in shallow water and wet mud areas with a high density of Vallisneria spp. tubers. Given their preference for shallow water habitats, plus the fact that no cranes use deep-water lakes with heavily controlled water levels such as at Junshan Hu and Qinglan Hu, we conclude that our survey, as well as previous surveys (Li et al., 2011), provides insight into the potential impact from large-sized water projects in the Poyang Lake basin. Water control projects have been proposed in order to keep higher water levels in winter, possibly limiting access to submerged macrophytes by wintering waterbirds and reducing variation in the system. Under these conditions, a lack of macrophyte foraging habitat and chronic shortages of accessible Vallisneria could contribute to a reduction in the reproduction ability of this species and, ultimately, to extirpation in the wild of the Siberian Crane, because no other available winter habitat is known for this species (Barzen et al., 2011).

The survey was conducted by staff members from Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve (PLNR), Nanjishan National Nature Reserve and Duchang Migratory Birds Nature Reserve. Yifei Jia from Beijing Forestry University participated in parts of the survey. Financial support for the survey was provided by several ICF directors and the Disney Worldwide Conservation Fund.

|

Barter M, Chen LW, Cao L, Lei G. 2004. Waterbird survey of the middle and lower Yangtze River floodplain in late January and early February 2004. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, p 102.

|

|

Barter M, Lei G, Cao L. 2005. Waterbird survey of the middle and lower Yangtze River floodplain in February 2005. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, p 64.

|

|

Barzen J, Burnham JW, Li FS, Harris J. 2011. How do Siberian Cranes and other tuber feeding birds respond to a flood-induced lack of tubers at Poyang Lake. Wetlands, 4: 6-8.

|

|

Burnham JW, Barzen JA. 2007. Final technical report on preliminary data trends at multiple scales at Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve: 1998-2005. Siberian Crane Wetland Project: Regional Program Report 2712-3-4645.

|

|

Burnham JW. 2007. Environmental drivers of Siberian crane (Grus leucogeranus) habitat selection and wetland management and conservation in China. M.S. Thesis. University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA, p 111.

|

|

Callahan JT. 1984. Long-term ecological research. Bioscience, 34(6): 363-367.

|

|

Cui XH, Zhong Y Chen JK. 2000. Influence of a catastrophic flood on densities and biomasses of three plant species in Poyang Lake, China. J Freshwater Ecol, 15: 537-541.

|

|

Gil de Weir, K. 2006. Whooping Crane (Grus americana) demography and environmental factors in a population growth simulation model. Ph. D. Dissertation. Texas A & M University. College Station, USA, p 158.

|

|

Goroshko O. 2012. Global climate change and conservation of cranes in the Amur River basin. In: Harris J (ed) Proceedings of the Cranes-Climate-People Workshop, Muraviovka Park, Russia, 28 May-3 June 2010. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA.

|

|

Harris J. 2000. Siberian Cranes in old rice paddies by Poyang Lake. In: Li FS (ed) 2000 China Program Reports. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA, pp 63-67.

|

|

Huang JG. 2011. Behavioral time budget of the overwintering Tundra Swans in the Poyang Lake. Undergraduate Student Project Paper. Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, p 12. (in Chinese)

|

|

Huang SE. 2000. Monitoring seasonal changes in water bodies of Poyang Lake using satellite images. In: Liu XZ, Ye JX (eds) Jiangxi's Wetlands. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, pp 263-267. (in Chinese)

|

|

Ji WT, Zen NJ, Wang YB, Gong P, Xu B, Bao SM. 2007. Analysis of the waterbirds community survey of Poyang Lake in winter. Annal GIS, 13(1/2): 51-64.

|

|

Ji WT, Zeng NJ, Wu JD, Wu XD, Yi WS. 2002. Aerial survey. In: Wu YH, Ji WT (eds) Study on Jiangxi Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, pp 157-166. (in Chinese)

|

|

Li FS, Burnham B. 2008. Juvenile Recruitment rate of Siberian Cranes wintering at Poyang Lake in Winter 2007. China Crane News, 12(1): 21-22. (in Chinese)

|

|

Li FS, Ji WT, Zeng NJ, Wu JD, Wu XD, Yi WS, Huang ZY, Zhou FL, Barzen J, Harris J. 2005. Aerial survey of Siberian Cranes in the Poyang Lake Basin. In: Wang QS, Li FS (eds) Crane Research in China. Yunnan Education Publishing House, Kunming, pp 49-57. (in Chinese)

|

|

Li FS, Wu JD, Zeng NJ, Ji WT, Wu XD, Yi WS, Huang ZY, Zhou FL, Barzen J, Harris J. 2011. Number and distribution of large waterbirds determined by aerial surveys from 1998-2000 at Poyang lake. In: Li FS, Liu GH, Wu JD, Zeng NJ, Harris J, Jin JF (eds) Ecological Study of Wetlands and Waterbirds at Poyang Lake. Popular Science Press, Beijing, pp 106-118. (in Chinese)

|

|

Liu GH, Zeng NJ, Wu JD, Wen SB, Gao X, Wang YB. 2011. Number and distribution of waterbirds determined by ground survey in winter of 2006. In: Li FS, Liu GH, Wu JD, Zeng NJ, Harris J, Jin JF (eds) Ecological Study of Wetlands and Waterbirds at Poyang Lake. Popular Science Press, Beijing, pp 144-152. (in Chinese)

|

|

Liu XZ, Ye JX. 2000. Jiangxi's Wetlands. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, p 331. (in Chinese)

|

|

Liu YZ, Jia DJ. 2000. Report on the distribution of Siberian Cranes at Poyang Lake in November, 1999. China Crane News, 4(2): 4. (in Chinese)

|

|

Meine CD, Archibald GW. 1996. The cranes: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN, Gland Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, p 294.

|

|

Nichols JD, Williams BK. 2006. Monitoring for conservation. Trend Ecol Evol, 21(12): 668-673.

|

|

Nolet BA, Bevan RM, Klaassen M, Langevoord O, van Der Heijden YGJT. 2002. Habitat switching by Bewick's swans: maximization of long-term energy gain? J Animal Ecol, 71: 979-993.

|

|

Prange H. 2012. Reasons for changes in crane migration patterns along the west-European flyway. In: Harris J (ed). Proceedings of the Cranes-Climate-People Workshop, Muraviovka Park, Russia, 28 May-3 June 2010. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA.

|

|

Qian FW, Jiang HX, Wu ZG, Li XM. 2009. Waterbird monitoring along flyway of Siberian Cranes in China. In: Prentice C (ed) Conservation of Flyway Wetlands in East and West/Central Asia. Proceedings of the Project Completion Workshop of the UNEP/GEF Siberian Crane Wetland Project, 14-15 October 2009, Harbin, China. International Crane Foundation, Baraboo, Wisconsin, USA.

|

|

Qian FW. 2003. Siberian Crane wintering in China in 2002/03. Siberian Crane Flyway Newsletter, 4: 4.

|

|

Shankman D, Davis L, De Leeuw J. 2009. River management, landuse change, and future flood risk in China's Poyang Lake region. Int J River Basin Manage, 7(4): 423-431.

|

|

Wu YH, Ji WT (eds). 2002. Study on Jiangxi Poyang Lake National Nature Reserve. China Forestry Publishing House, Beijing, pp 231.

|

|

Yan MH, Liu ST, Zhang W, Zong C, Lou J. 2012. Climate change and its impacts on ecological environment in Hulun Lake Area. Science Press, Beijing, p 243. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zhou FZ, Ding WN. 1982. On the wintering habits of White Crane (Grus leucogeranus). Chin J Zool, 17(4): 19-21. (in Chinese)

|

|

Zhu HH, Zhang B. 1997. Poyang Lake-hydrology, biology, sediment, wetland, and development/mitigation. University of Science and Technology of China Publishing House, Hefei, China, p 349. (in Chinese)

|

| Species | 18–19 December 2011 | 18–19 February 2012 |

| Siberian Crane | 4577 | 3335 |

| White-naped Crane | 885 | 283 |

| Hooded Crane | 302 | 110 |

| Eurasian Crane | 8408 | 2205 |

| Total | 14172 | 5933 |

| Winter | Survey dates | Siberian Crane | White-naped Crane | Air/ground survey | Source of data |

| 1980/81 | Unknown | ~100 a | – b | Ground | Zhou and Ding (1982) |

| 1981/82 | Unknown | 91 a | – | Ground | Zhou and Ding (1982) |

| Unknown | 140 | – | Aerial | Zhou and Ding (1982) | |

| 1996/97 | Jan–Mar 1997 | 2345 | 2470 | Aerial | Ji et al. (2002) |

| 1998/99 | 11–12 Dec 1998 | 2004 | 870 | Aerial | Li et al. (2005) |

| 7 Jan 1999 | 2536 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) | |

| 16–17 March 1999 | 932 | 630 | Aerial | Li et al. (2005) | |

| 1999/00 | 11–15 Nov 1999 | 3643 | 3209 | Ground | Liu and Jia (2000) |

| 26–27 Feb 2000 | 897 | 1035 | Aerial | Li et al. (2005) | |

| 2000/01 | 9–14 Feb 2001 | 3008 | 4354 | Aerial | Ji et al. (2002) |

| Feb 2001 | 2087 | 2943 | Ground | Ji et al. (2002) | |

| 8 Jan 2001 | 1791 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) | |

| 2001/02 | 9 Jan 2002 | 3404 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) |

| 2002/03 | 9 Jan 2003 | 4004 | – | Ground | Qian (2003) |

| 2003/04 | Late Jan–early Feb 2004 | 2746 | 2713 | Ground | Barter et al. (2004) |

| 2004/05 | 14–28 Feb 2005 | 2683 | 1491 | Ground | Barter et al. (2005) |

| 2005/06 | – | 3131 | 1568 | Aerial | Li et al. (2011) |

| 2006/07 | 15–23 Dec 2006 | 2715 | 1757 | Ground | Liu et al. (2011) |

| 2008/09 | Feb 2009 | 3003 | 1017 | Aerial | Li et al. (2011) |

| 2011/12 | 18–19 Dec 2011 | 4577 | 885 | Ground | This study |

| 19–19 Feb 2012 | 3335 | 283 | Ground | This study | |

| a only covered the western part of the lake basin; b no data. | |||||