| Citation: | Tonya M. Haff, Natalie Tees, Kathryn Wood, E. Margaret Cawsey, Leo Joseph, Clare E. Holleley. 2021: Collection, curation and the use of humidification to restore nest shape in a research museum bird nest collection. Avian Research, 12(1): 34. DOI: 10.1186/s40657-021-00266-5 |

Bird nests are an important part of avian ecology. They are a powerful tool for studying not only the birds that built them, but a wide array of topics ranging from parasitology, urbanisation and climate change to evolution. Despite this, bird nests tend to be underrepresented in natural history collections, a problem that should be redressed through renewed focus by collecting institutions.

Here we outline the history and current best practice collection and curatorial methods for the nest collection of the Australian National Wildlife Collection (ANWC). We also describe an experiment conducted on nests in the ANWC using ultrasonic humidification to restore the shape of nests damaged by inappropriate storage.

The experiment showed that damaged nests can be successfully reshaped to close to their original dimensions. Indeed, restored nests were significantly closer to their original shape than they were prior to restoration. Thus, even nests damaged by years of neglect may be fully incorporated into active research collections. Best practice techniques include extensive note taking and photography in the field, subsampling of nests that cannot or should not be collected, appropriate field storage, metadata management, and prompt treatment upon arrival at the collection facility.

Renewed focus on nest collections should include appropriate care and restoration of current collections, as well as expansion to redress past underrepresentation. This could include collaboration with researchers studying or monitoring avian nesting ecology, and nest collection after use in bird species that rebuild anew each nesting attempt. Modern expansion of museum nest collections will allow researchers and natural history collections to fully realise the scientific potential of these complex and beautiful specimens.

Nest predation is the most important factor impeding successful breeding in birds (Ricklefs 1969; Martin 1995; Caro 2005; Lima 2009). Under such selection pressure, birds have evolved complex anti-predation strategies to protect their nests and perform specific nest defence behaviours when facing different types or risk levels of predators (Lima et al. 2005; Yorzinski and Vehrencamp 2009; Yorzinski and Platt 2012; Mahr et al. 2015; Suzuki 2015; Maziarz et al. 2018). Although nest defence by parents can increase the survival possibility of offspring, it also costs defenders in terms of time and energy expenditure and injury or death caused by predators (Montgomerie and Weatherhead 1988). Both underestimating or overestimating the danger posed by a predator can be detrimental for parents (Caro 2005). Therefore, parent birds should choose the right nest defence strategy when defending their offspring against predators, including making a decision about whether and how intensively to defend their nests (e.g. Caro 2005; Mahr et al. 2015).

Distinguishing different predators and their threat levels is the first step to effectively avoid predators. The body size of a predator is a reliable indicator of the threat level that it poses to birds (Swaisgood et al.1999), and it is especially important in some predators that they are quite similar in overall appearance as well as body shape (Beránková et al. 2014). It has been shown that various bird species can distinguish between raptors differing in size and then perform appropriate antipredator response behaviours (Evans et al. 1993; Templeton et al. 2005; Courter and Ritchison 2010). However, many factors, such as habitat, nest stage, sex, nest type and predator location, may influence and cause changes in nest defence behaviour of birds (Burger 1992; Ritchison 1993; Møller et al. 2016; Crisologo and Bonter 2017). For example, alarm calling rates increased with the nesting stage in Southern House Wrens (Troglodytes musculus) (Fasanella and Fernández 2009).

Generally, cavity-nesting birds are better protected against nest predator's attacks than open-cup nesters (Martin and Li 1992), as nest entrance can play a role in preventing predator's access to nests (Wesołowski 2002). However, nest predation is still the main cause of reproductive failure for cavity-nesting species (Lima 2009). Some predators can enter the nest cavity if the entrance of a hole is sufficiently large, such as chipmunks, snakes and small owls (Solheim 1984; Suzuki 2011; Yu et al. 2020). A cavity with a small entrance size can prevent more predators from entering and plundering the nest than a cavity with a large entrance size (Wesołowski 2002). Therefore, the body size of a nest predator, in theory, should indicate the level of threat that they pose to cavity-nesting birds.

Secondary cavity-nesting species are unable to excavate their own nest holes, and they depend on cavities created by primary excavators (e.g., woodpeckers) and natural decay processes (Newton 1994). Most secondary cavity-nesting species build their nests, which are placed at the base of the cavity, and do not adjust the entrance of holes, such as the Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata). Several Sitta nuthatches have the ability to narrow the cavity entrance by plastering mud around the openings (Matthysen 1998; Wesołowski and Rowiński 2004; Strubbe and Matthysen 2009). In theory, a smaller entrance hole size should give nuthatches an advantage as protection against larger predators (Wesołowski 2002). However, few studies have tested whether narrowing the entrance hole size can affect the estimation of threat levels from nest predators in cavity-nesting birds.

Eurasian Nuthatches (Sitta europaea, nuthatches hereafter) breed in nest boxes (the range of the entrance hole size was 4.5 to 6.5 cm, see details below) in our study area. They usually narrow the entrance hole of a nest box to approximately 2.5 cm by using mud. Common Chipmunks (Tamias sibiricus, chipmunk hereafter) and Red Squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris, squirrel hereafter) are nest predators of nesting cavity, as they enter nests to destroy the nest cup and eat the eggs and chicks. Chipmunks can enter most nest boxes easily due to their small body size (head-and-body length is approximately 130 cm), but squirrels (approximately 200 cm, Piao et al.2013) are rarely found in nest boxes with entrance hole sizes < 4.5 cm. Here, we tested whether Eurasian Nuthatches perform different nest defence behaviours against chipmunks and squirrels according to their adjusted entrance hole size. If mud around the entrance prevents nest predators from entering, we expected nuthatches to exhibit stronger nest defence behaviours in chipmunks than in squirrels.

Our experiments were carried out in Zuojia Nature Reserve (44°1′–45°0′ N, 126°0′–126°8′ E) in Jilin, northeastern China. The vegetation within the study area was diverse, with a continental monsoon climate and four distinct seasons in the temperate zone, although the existing forest was secondary (E et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019). We attached nest boxes to trees approximately 3–4 m above the ground, and the number of nest boxes distributed in Zuojia was maintained at approximately 450 per year (Yu et al. 2017a). The entrance hole size of an original artificial nest box in our study area was 4.5 cm. However, woodpeckers often peck holes in nest boxes, which results in expansion of the entrance hole size up to a maximum of 6.5 cm. If a pecked nest box can still be used by birds, we will not replace it. Thus, the range of the entrance hole size of an artificial nest box in our study area was 4.5 to 6.5 cm.

During the breeding season, the total number of nests used by birds in the study area was approximately 180 (including 10–20 pecked nest boxes) per year. In addition to secondary cavity-nesting birds, rodent chipmunks and squirrels are also bred in artificial nest boxes. Based on our observations, the population size of squirrels was slightly larger than that of chipmunks. The numbers of nest boxes used by chipmunks and squirrels were approximately 10–15 nests and 1–2 nests per year, respectively. The nest boxes were checked at intervals of 5–7 days from March to July to determine occupancy, and we classified boxes with at least one egg as occupied (E et al. 2019).

Previous studies found that nuthatches exhibit significantly different nest defence behaviours than terrestrial and aerial nest predators (Matthysen 1998; Sun et al. 2017; Nad'o et al. 2018). They usually exhibit specific aggressive behaviours in terrestrial vertebrates, such as hovering over and spreading out wings and tails (Sun et al. 2017). Therefore, we did not pose any other species dummy to nuthatches as a neutral or negative control in this study. Instead, we chose another cavity-nesting bird species, Cinereous Tits (Parus cinereus, tits hereafter), as a positive control. Nuthatches and tits are small cavity-nesting birds with similar body sizes. Tits do not adjust the entrance hole, while nuthatches use mud to narrow the entrance. Here, we compared the intensity of defence behaviours of nuthatches and tits to the same nest predators.

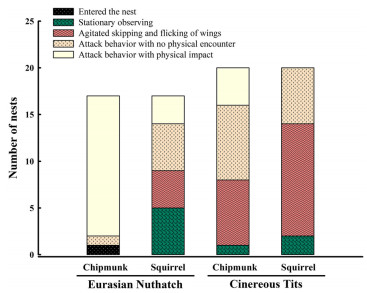

During the nestling period of Eurasian Nuthatches (n = 17 nests) and Cinereous Tits (n = 20 nests, 6 of the 20 nesting boxes were pecked by woodpeckers), we presented taxidermic dummies of Common Chipmunks (small nest predator, 2 models) and Red Squirrels (large nest predator, 2 models) above the nest boxes. The trials were conducted during sunny days between 8:30 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., from May 10 to June 1, 2019, and each nest received two dummy presentations in a random order. Video recorders were set up to record the experimental process. We scored the dummy responses (response scores hereafter) of nuthatches and tits on a five-point scale: (ⅰ) entered the nest; (ⅱ) produced alarm calls during stationary observation; (ⅲ) produced alarm calls with agitated skipping and flicking of wings; (ⅳ) approached the rodent closely and hovered over it, spreading their wings and tail, or performed attack behaviour with no physical encounter; and (ⅴ) performed attack behaviour with physical impact (Liang and Møller 2015; Yu et al. 2017a; 2019). As the birds often attacked nest predators, we also quantified aggressive behaviour by counting the number of contact attacks of focal parent birds (attack numbers hereafter, we counted the exact number of attacks indoors by playing back the video). This enabled us to determine the primary target of attacks of the defending parents.

All data were analysed using R 3.6.1 software (http://www.r-project.org). For the response scores (ranked response, 5 levels) of nuthatches and tits, cumulative link mixed models (CLMMs, clmm in R package ordinal) with logit-link function were used, and we used two-tailed likelihood ratio tests to obtain P values. For attack numbers of nuthatches and tits, generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs, glmer in R package lme4) with a Poisson error structure and log-link function were used, and we calculated P values using Wald Chi-square tests with the Anova function in the car package. In the model, response scores or attack numbers were the dependent variable, whereas bird species, treatment and order of treatment exposure were treated as fixed terms, and individuals distinguishing birds' nests were random terms. If there was a significant effect of bird species and treatment, we further performed post hoc pairwise comparisons between species and treatments. To reduce the probability of type I errors, Bonferroni correction was used to adjust P values (P.adjust function in the R package stats, Rice 1989; Yu et al. 2017b).

The dummy response scores of nuthatches and tits differed significantly between species (CLMMs, χ21 = 10.50, P = 0.001) and treatments (χ21 = 20.16, P < 0.001), while there were no significant effects of trial order (χ21 = 0.02, P = 0.88) on dummy response scores. The dummy response scores of nuthatches (adjusted P < 0.001) and tits (adjusted P = 0.047) were sufficiently stronger to chipmunks than to squirrels (Fig. 1). In addition, the dummy response scores of nuthatches to chipmunks were sufficiently stronger than those of tits to chipmunks (adjusted P < 0.001). The dummy response scores of nuthatches and tits to squirrels were similar (adjusted P = 1.000).

The number of attacks of nuthatches and tits differed significantly between species (GLMMs, χ21 = 12.96, P < 0.001) and treatments (χ21 = 63.52, P < 0.001), while there were no significant effects of trial order (χ21 = 2.52, P = 0.11) on attack numbers. Nuthatches attacked chipmunks significantly more strongly than squirrels (adjusted P < 0.001, Fig. 2). In contrast, tits rarely attacked chipmunks and squirrels (adjusted P = 1.000). The number of attacks of nuthatches to chipmunks were greater than those of tits to chipmunks (adjusted P = 0.001). The number of attacks of nuthatches and tits to squirrels were similar (adjusted P = 1.000).

In our study, both nuthatches and tits exhibited stronger response behaviours (high dummy response scores) to chipmunks than to squirrels. For parents, nest defence behaviours (e.g., defensive displays and direct attacks) may enhance their reproductive success (Montgomerie and Weatherhead 1988). However, decision-making in active nest defence is quite a complex process, and threat levels of predators to broods should be taken into account (Kleindorfer et al. 2005). Chipmunks and squirrels pose the same kind of nest predation threat to cavity birds, as they can enter nests to destroy the nest contents. However, chipmunks are major nest predators in our study area, and squirrels may occasionally exhibit opportunistic omnivory. Even nuthatches used mud to narrow their entrance hole, which could completely prevent squirrels but not chipmunks from entering because chipmunks could remove a part of the mud to gain access to enter the cavity (Wesołowski 2002). Our study results indicated that nuthatches and tits could discriminate rodents differing in size, and the predatory threat of chipmunks to their offspring was higher than that of squirrels.

The number of attacks could reflect the degree of aggressiveness of the attacks (Fuchs et al. 2019). In our study, nuthatches attacked chipmunks significantly more strongly than squirrels (Fig. 2), while tits rarely attacked them. Parents attacking nest predators directly may be more efficient and result in successfully deterring predators from the brood. However, anti-predator behaviour is usually energetically taxing (Krams and Krama 2002), and defending parents experience risk of injury or death (Brunton 1986; Montgomerie and Weatherhead 1988; Sordahl 1990). Here, specific attacking behaviours against the more dangerous chipmunks were most likely an anti-predator strategy for nuthatches, which may help them to reduce the energy costs of unnecessary aggressive behaviours (Polak 2013; Kryštofková et al. 2011; Yu et al. 2016). Based on our field observations, tits were unlikely to succeed in protecting their nest contents from invading nest predators by performing aggressive behaviours. Then, enacting displays with a moderate or low degree of aggression to nest predator chipmunks and squirrels could enable tits to avoid unnecessary investment in costly attacks (Polak 2013).

In this study, dummy response scores and attack numbers of nuthatches to chipmunks were significantly higher than those of tits to chipmunks, while the response behaviours of nuthatches and tits to squirrels were similar. Parental behaviours are selected to maximize lifetime reproductive success, and nest defence intensity of parent birds will also be influenced by the benefit for the current brood versus future reproduction (Trivers 1972; Smith 1977). Both Eurasian Nuthatches and Cinereous Tits are short-lived birds and have similar lifespans, but the possibility of repeating a lost brood during one breeding season differs between them. The population of Cinereous Tits in our study area can produce a second brood immediately after the failure of the first brood effort, while Eurasian Nuthatches only produce one large brood per year. Thus, nuthatches should have a stronger incentive to attempt to drive dangerous nest predators away through active nest defence behaviours (Curio 1978) because saving energy for future broods is a rather unlikely strategy. For tits, the probability of re-nesting may play a major role in their risk taking; therefore, they might be at less risk for their current brood than a bird with a lower re-nesting potential (Curio et al. 1984; Ghalambor and Martin 2000, 2001).

Nuthatches and tits exhibited different nest defence behaviours against the same nest predators, and the results showed that those two species implemented different nest defence strategies. If a nest intruder does not represent an immediate threat to the nest, it is more advantageous for nest owners to refrain from aggressive behaviour (Kryštofková et al. 2011). Moreover, the compromise between current and future reproduction should be taken into account for defence intensity towards a threat posed to the offspring (Caro 2005). Results of the present study suggested that nuthatches might estimate threat levels of nest predators according to their narrowed entrance-hole size. Future studies should determine if mud around the entrance can play an important role in preventing nest predators with different sizes from entering, which in turn may help us to understand the functions of plastering mud in nuthatches.

We are grateful to Dongxu Li and Junlong Yin for assistance with fieldwork. We also thank Zuojia Nature Reserve for their support and permit to carry out this study.

HW, KZ and J. Yu conceived the idea and formulated questions. JF, GY and CS performed the experiments. JF and LZ analyzed data. J. Yu and LZ wrote the manuscript. J. Yao contributed substantial materials. HW, KZ and J. Yu contributed resources and funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The experiments comply with the current laws of China. Fieldwork was carried out under the permission from Zuojia Nature Reserves, Jilin, China. Experimental procedures were permitted by National Animal Research Authority in Northeast Normal University (Approval Number: NENU–20080416) and the Forestry Bureau of Jilin Province of China (Approval Number: [2006]178).

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

|

Alper D. How to flatten folded or rolled paper documents. National Park Service Conserve O Gram. 1993;13: 1–4.

|

|

Bendire C. Directions for collecting, preparing, and preserving birds' eggs and nests. Bull U S Natl Mus. 1891;Part D: 3–10.

|

|

Clark T. Conservation of an Aboriginal wallaby skin water bag at the Australian museum. In: Fogle S, editor. Recent advances in leather conservation. Proceedings of a refresher course. Washington: The Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation; 1984.

|

|

Cruikshank P, Saiz GV. An early gut parka from the Arctic, its past and current treatment. Prepared for the ICON-ethno workshop scraping gut and plucking feathers: the deterioration and conservation of feather and gut materials. York: University of York; 2009.

|

|

Darwin C. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray; 1871.

|

|

Deeming DC, Reynolds SJ. Nests, eggs, and incubation: new ideas about avian reproduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

|

|

Hansell M. Bird nests and construction behaviour. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

|

|

Hansell M. Built by animals: the natural history of animal architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

|

|

Goodfellow P. Avian architecture: how birds design, engineer and build. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2011.

|

|

Green RE, Scharlemann JPW. Egg and skin collections as a resource for long-term ecological studies. Bull BOC. 2003;123A: 165–76.

|

|

International Labour Organization (ILO). Phosphine: International Chemical Safety Card 0694. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2017.

|

|

Jackson K, Andrew H. Gut reaction: the history, treatment and isplay techniques of gut garments at the Pitt Rivers Museum. Prepared for the ICON-ethno workshop scraping gut and plucking feathers: the deterioration and conservation of feather and gut materials. York: University of York; 2009.

|

|

Mason IJ, Pfitzner GH. Passions in ornithology: a century of Australian egg collectors. Canberra: Andrew Isles Natural History Book; 2020.

|

|

Prism G. version 6.04 for Windows. California: GraphPad Software; 2015.

|

|

Ralph CJ, Geupel G, Pyle P, Martin TE, DeSante DF. Handbook of field methods for monitoring landbirds. Albany: Pacific Southwest Resaerch Station; 1993.

|

|

Rulik B, Kallweit U. A blackbird's nest as breeding substrate for insects—first record of Docosia fumosa Edwards, 1925 (Diptera: Mycetophilidae) from Germany. Studia Dipterologica. 2006;13: 41–3.

|

|

Soniat TJ. Assessing levels of DNA degradation in frozen tissues archived under various preservation conditions in a natural history collection. Lubbock: Texas Tech University; 2019.

|

|

Wallace AR. Darwinism: an exposition of the theory of natural selection, with some of the applications. London: MacMillan; 1889.

|

|

Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer; 2016.

|

|

Wiedenfeld DA. A nest of the Pale-billed Antpitta (Grallaria carrikeri) with comparative remarks on antpitta nests. Wilson Bull. 1982;94: 580–2.

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO). Phosphine and selected metal phosphides. Environmental health criteria. Geneva: WHO; 1988.

|

| 1. | Qingzhen Liu, Jiangping Yu, Romain Lorrillière, et al. Effects of local nest predation risk on nest defence behaviour of Japanese tits. Animal Behaviour, 2025, 219: 123031. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2024.11.009 |

| 2. | Xudong Li, Jiangping Yu, Li Zhang, et al. Nest site selection during the second breeding attempt in Japanese tits (Parus minor): effects of nest site characteristics. Scientific Reports, 2025, 15(1) DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-87928-2 |

| 3. | Nehafta Bibi, Qingmiao Yuan, Caiping Chen, et al. Three cases of collared owlet depredation on the green‐backed tit within nest boxes. Ecology and Evolution, 2024, 14(3) DOI:10.1002/ece3.11083 |

| 4. | Mingju E, Jiangping Jin, Yu Luo, et al. The Japanese tits evaluate threat level based on the posture of a predator. Scientific Reports, 2024, 14(1) DOI:10.1038/s41598-024-73124-1 |

| 5. | Dake Yin, Jiangping Yu, Jiangping Jin, et al. Nest box entrance hole size can influence nest site selection and nest defence behaviour in Japanese tits. Animal Cognition, 2023, 26(4): 1423. DOI:10.1007/s10071-023-01791-0 |

| 6. | Mark T. Stanback, Maxwell F. Rollfinke. Tree Swallows (Tachycineta bicolor) do not avoid nest cavities containing the odors of house mice (Mus musculus). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 2023, 135(1) DOI:10.1676/22-00045 |

| 7. | Xudong Li, Jiangping Yu, Dake Yin, et al. Using radio frequency identification (RFID) technology to characterize nest site selection in wild Japanese tits Parus minor. Journal of Avian Biology, 2023, 2023(7-8) DOI:10.1111/jav.03108 |

| 8. | Li Zhang, Jiangping Yu, Chao Shen, et al. Geographic Variation in Note Types of Alarm Calls in Japanese Tits (Parus minor). Animals, 2022, 12(18): 2342. DOI:10.3390/ani12182342 |