| Citation: | Oleg A. GOROSHKO. 2012: Red-crowned Cranes on the Russian-Chinese Argun River and neighboring parts of the Daurian steppes. Avian Research, 3(3): 230-237. DOI: 10.5122/cbirds.2012.0022 |

The Trans-Baikal geographical region is located in southeastern Siberia, Russia, east towards Lake Baikal and include the Daurian steppes. The steppes provide important habitats for several species of cranes, including the Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis). I have studied the cranes in the area since 1988. The Red-crowned Crane mainly occurs in the Torey Depression (Torey Lake) and the Argun River, which represent the far western edge of the breeding area for the continental population of the Red-crowned Crane. There are some scattering records of the cranes in the Torey Depression from before 1990. The birds appeared regularly and bred from 2002-2007 at Torey Lake. There have been no records since 2008 due to the fact that the wetlands have dried out during the regional climate cycle in the Torey Depression. Three or four individual Red-crowned Cranes have been sighted in Argun in the early 2000's and then the numbers increased steadily until 2004. At the highest peak in 2004, there were at least 30 pairs of the cranes breeding in the wetlands of the river floodplain. Since then, with the reduced water flow in the Argun River and more and more wetlands drying out, the Red-crowned Crane population decreased dramatically to four or seven territories. The cranes are facing serious threats in the Argun River, such as frequent spring fires, poaching and water pollution. We need to unify efforts from both the Russian and Chinese sides to protect the cranes and their wetland habitat in the area.

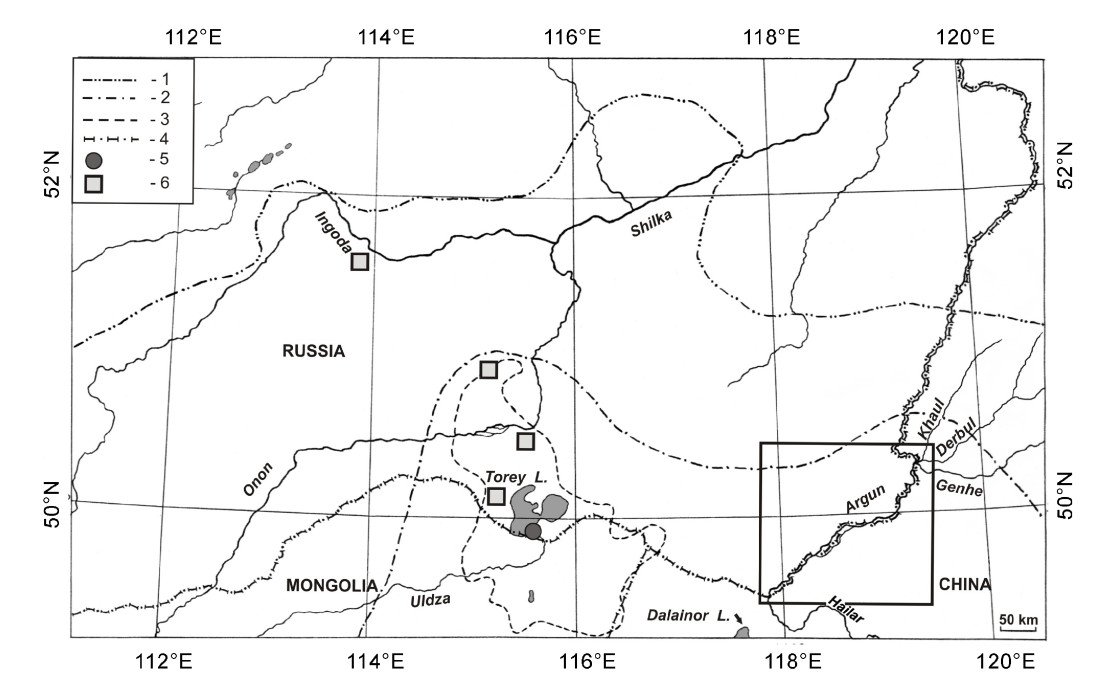

The Trans-Baikal geographical region is located in southeastern Siberia, Russia, east towards Lake Baikal. The eastern part of the Trans-Baikal region is Zabaikalsky Kray (Zabaikalsky Region), formed in 2008 by the fusion the former Chita Region and the Aginsky Buriat Autonomous Region. The main part of Zabaikalsky Kray includes vast forests; the southeastern part near the border with China and Mongolia includes the Daurian steppes (Fig. 1). These steppe and forest-steppe areas provide important habitats for several species of cranes, including the Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis), White-naped (G. vipio), Common (G. grus) and Demoiselle (Anthropoides virgo), and this area represents the far western edge of the breeding area for the continental population of the Red-crowned Crane. The first three cranes use similar habitats — extensive open wetlands including reeds and sedge meadows with shallow water, usually in river valleys. The Red-crowned Crane prefers the wettest habitats that are present only on the Argun.

Up to the late 20th century there was no information available about the existence of Red-crowned Cranes in the Trans-Baikal Region. Only a single record, probably of a vagrant bird in the vicinity of Darasun Village (51°39′N, 113°58′E), was mentioned by L.M. Shulpin (1936); the exact date and location of this record is not known. None of the other researchers mentioned this species but they recorded White-naped Cranes on the Argun River, the Torey Lakes and other sites of the southeastern Trans-Baikal region (Pallas, 1788; Radde, 1863; Taczanowski, 1893; Stegmann, 1929; Gavrin and Rakov, 1959, 1960). Hence, it could be concluded that in the past, the Red-crowned Crane probably was a rare vagrant species in Dauria.

In southeastern Zabaikalsky Kray, investigation of cranes occurred irregularly in the mid 1970s and more often during the 1975–1987 period, while thorough research has been conducted since 1988. There has been almost no detailed report about Red-crowned Cranes in the Trans-Baikal Region until recently. The main habitats of the Red-crowned Cranes on the Argun River had not been well studied until the last few years. I started ornithological investigations on the upper Argun River in 2004. The main aim of my work was to study the status of its population and threats to globally threatened species of waterbirds. The Red-crowned Crane was the focus of my study because the Argun was found to be an internationally important and vulnerable breeding site for this species. The study reveals profound changes of the local crane population during the last few decades.

The Daurian steppes extend from northeastern Mongolia and adjacent regions of northeastern China into the southern Trans-Baikal Region, Russia (Fig. 1). Dauria is an internationally important area for six globally threatened species of waterbirds (IUCN, 2011) including Red-crowned and White-naped (G. vipio) Cranes.

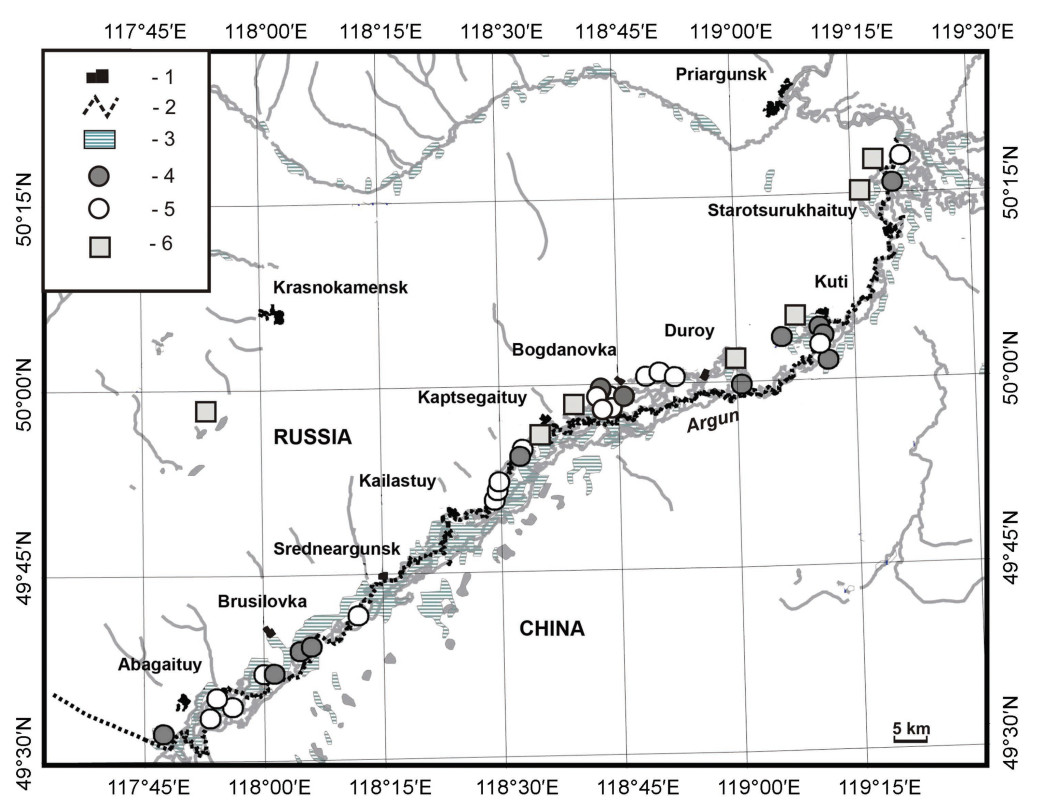

There are two main nuclei of biodiversity and main crane sites in Dauria: the Torey Lakes and the Argun River (Fig. 2). The Torey Lakes are the largest lakes in the Trans-Baikal region. The most important wetlands are located in the part of the Argun about 150 km along from its origin (49°32′N, 117°50′E) to the joint mouth of three Chinese tributaries: the Genhe, Derbul and Khaul rivers (50°20′N, 119°22′E). The Argun is largest river in the Dauria steppe area. It is a transboundary river located between Russia and China. Its upper part, in China, is called the Hailar River. This upper part of the Argun is located in a flat steppe zone, where it forms a very wide (6 km at average, 15 km at maximum) and wet valley. This valley provides habitats for hundreds of thousands of breeding and millions of migratory waterbirds, consisting of extensive wet sedge and grass meadows and reeds (Goroshko, 2007a, 2007b). The middle and lower reaches of the Argun are located in the forest-steppe and forest zones, flowing among high hills through a narrow valley with few wetlands. The Torey Lakes are protected in the the Daursky Nature Reserve that is part of the Dauria International Chinese-Mongolian-Russian Protected Area. The Argun River is not protected on the Russian side.

The ecosystems in Dauria depend significantly on long-term climatic cycles (of about 30-year duration) with interchanging wet and dry periods (Obiazov, 1994; Goroshko, 2002). These cycles have a great effect on the amount of precipitation, on the condition of wetlands and hence on the population of cranes and other waterbirds. During the 1982–1998 period rainfall increased, but since 1999 it has decreased. During the 2000–2007 period, the area of wetlands decreased quickly. In May–June 2008 and 2009, the area of wetlands in Dauria was only about 2% of the wetland area found in 1998 so, by far, the major part of the habitat of cranes and other waterbirds (steppe lakes and rivers) was completely dry. The dynamics of steppe lakes reflect the cyclical pattern of precipitation in the Dauria region.

The dynamics of the Argun are less dependent on precipitation in the Dauria region; they differ somewhat from those of other steppe rivers and lakes because the upper part of the Hailar-Argun River originates from the Great Khingan (Xingan) mountains outside the Dauria steppe region. During my study period, the spring water level decreased steadily in the Argun River from 2004 to 2011. In the early summer of 2008, the water level was the lowest during the entire period of official hydrological monitoring of this river (Fig. 3).

I studied cranes in the Daurian steppes in Russia during from 1988 to 2011 and have surveyed about 90% of the steppe zone and 60% of the forest-steppe zone. The total length of the survey route is about 48000 km and covers about 115000 km² from the state borders with Mongolia and China northward to the Shilka and Ingoda rivers and from the upper Onon River eastwards to the Argun River. Before 2004, detailed observations were made in the southern and central parts of the Dauria region. The most thorough investigations were conducted on the Torey Lakes and Torey Depression while the eastern territories were observed insufficiently. The first data about birds of the Argun were secured by me in 1997 during field observations on the lower Argun and by questioning a few local people living along the upper part of this river. A second brief inquiry on the upper Argun was made in 2000. Since 2004, I have conducted detailed studies in the upper Argun by field observations of the valley and by questionnaires of local people.

The field observations were carried out by driving a car mainly along potential habitats of cranes, i.e., rivers, lakes and wet depressions. The cranes were counted with a binocular (× 8–10) and telescope (× 25–75). Usually I used the tops of hills near the wetlands, or sometimes stood on top of the car if there were no suitable hills nearby. Depending on vegetation in the wetlands, the height of hills and other conditions, I stopped every 3–8 km for complete and detailed (as far as possible) observations. I also studied threats. On the Argun, I observed the valley from the Russian side.

It is very difficult to see chicks in the Argun Valley because of its tall vegetation. Therefore, for recognition of the status of a recorded pair, I usually observed a pair for 1–3 h and only then was sure of their category: 1) non-territorial birds — a pair without its own territory, 2) breeding pair — a pair having nest with eggs or nestling(s) and 3) territorial non-breeding pair — a pair with its own territory but without eggs and nestlings. The third category included usually new pairs which only recently occupied their own new territory but had not yet started to breed and a breeding pair of lost egges or chicks. Annually, I made one or two observations per breeding season. During one observation, because of the restriction of my view, I was able to watch intensively only from 20% to 60% of birds at various sites on the Argun. The accuracy of my field survey results varied, depending mainly on absence or presence of hills and their height; it also depended on the width of the river valley. For my study of population dynamics, I used census data of highly accurate surveys on well-observed sites. For estimates of total population size on the Argun, I used extrapolation on badly observed and far-flung located suitable habitats.

During interviews, I asked local people about the location and number of cranes, use of habitat, conditions of wetlands, threats and other details. In total, I interviewed more than 1000 people in Dauria, including more than 250 hunters, herders and fishermen living along the upper Argun. During these interviews, I collected information about locations of territorial pairs. Then, I went to the field checking these locations to confirm the information provided. Only confirmed data are used in this paper. My conclusions about long term population dynamics of the crane are a combination of my field observations and results of the interviews.

Water data of the Argun came from the state hydrological-meteorological station located in Novotsurukhaituy Village (near Priargunsk Town).

There are some scattered records of non-breeding Red-crowned Cranes in the Torey Depression during the brief 1989–1991 period: 12 birds in 1989, seven birds in 1990 (Golovushkin and Goroshko, 1995) and one in 1991 (Golovushkin, unpubl. data). There are no records for the 1992–2001 decade in the Torey Depression and other Daurian steppes (excluding the Argun).

On 15 July 2002, four Red-crowned Cranes were observed at the Torey Lakes in the Uldza River Delta. It was the first record of this species in the Daursky Nature Reserve. That summer, four Red-crowned Cranes were also recorded in northeastern Mongolia in Sumber Somon, East Aimak. An unusual increase in numbers was also reported in the Daurian steppes in adjacent areas of China — eight non-breeding Red-crowned Cranes stayed at Dalai Lake during the 2002 nesting period (Goroshko et al., 2002). In 2003, two breeding Red-crowned Cranes and one single crane were recorded on the Torey Lakes in the Uldza River Delta. The pair successfully hatched two nestlings. During 2004–2007, the pair inhabited the delta, but had no successful breeding. No cranes were recorded there during 2008–2011. Four non-territorial Red-crowned Cranes were recorded on 16 June 2004 on a small steppe lake located 15 km southwest of Krasnokamensk Town (49°59′N, 117°55′E).

Some information about the Argun River was collected by interviews: one breeding pair of Red-crowned Cranes was seen on the Argun River in the vicinity of Kailastuy Village (Golovushkin and Goroshko, 1995), 10 birds were recorded near Bogdanovka Village in 1997, one pair with two chicks was recorded in 1998 between the Abagaituy and Brusilovka villages (Goroshko, 2002).

Along the upper Argun in 2004–2007, there were numerous sightings of Red-crowned Cranes. People have seen the cranes regularly since the early 2000s, often in the spring and autumn, sometimes in summer. Many of the pairs were territorial. During spring and summer, the cranes usually stayed in the wetlands of the river valley. In autumn they also often visited adjacent wheat crop fields and grasslands. Usually, local people saw pairs in April, single birds in May and groups of 3–4 birds in autumn. Figure 2 summarizes all data for locations of the territorial pairs and groups of non-breeding birds.

According to elderly hunters, the first few Red-crowned Cranes appeared on the upper Argun in about the mid 1970s near Kailastuy Village. After that, cranes probably were absent with some pairs appearing again in about the mid 1980s in the vicinity of Kailastuy and Kuti. During the period of the mid 1980s to the late 1990s, the number of the cranes increased. There were at least five pairs inhabiting the vicinity of Brusilovka, Kailastuy, Kaptsegaituy, Bogdanovka and Kuti during 1990–1995 and six to nine pairs in 1996–1999 based on information supplied by local people.

The number of the cranes increased quickly during 2001–2002; the numbers were continuing to grow in 2003–2004 but not as quickly. In 2004, there were at least 30 territorial pairs inhabiting the upper Argun. I was not able to locate the territories of another six pairs. At least 15 pairs of these birds bred, nine pairs probably bred, three pairs probably did not successfully breed while the status for the remaining birds was unknown. Among these birds, 22–24 pairs were located on Russian territory and 10–12 were on the Chinese side of the valley. I certainly missed some birds in the upper Argun valley because of difficult visibility and was unable to make a complete count for the Chinese side. I estimated the total number of cranes in 2004 as 45–70 territorial pairs, from both Russian and Chinese territories. There were also about 30 non-breeding cranes in flocks. These groups usually included up to 12 birds. They preferred to stay in slightly wet meadows in the valley, adjacent grasslands and on wheat fields.

The water level in 2004 was medium in the Argun, relative to other years and the valley included spacious wetlands. During the 2005–2008 period, the water level in the Argun decreased quickly and wetland areas were reduced. During the spring of 2009 habitat conditions were the worst — the size of wetlands was < 5% of that in 2004. Almost all crane habitats dried out. Accordingly, the number of cranes decreased dramatically during the years between 2005 and 2009. In 2008 and 2009, the number of territorial pairs was about 15% of that of 2004 — only two or three pairs were recorded in total on the Russian side. There were only a few pairs having wet nesting habitats. Nesting habitats for all remaining pairs had dried out or were insufficiently wet. Probably only one to three pairs were able to have chicks in 2008 and 2009. But I only recorded one successful breeding pair in each of those years. A big non-breeding flock with 26 birds was recorded in 2008. The flock remained in the vicinity of Abagaituy Village during the entire summer. I estimated the total number of cranes on the Russian and Chinese sides at about nine to fifteen territorial pairs in 2008 and 2009. The situation in 2010 and 2011 was the similarly bad or even worse. I have not seen any successful breeding in those years.

The Argun provides internationally important habitats not only for the Red-crowned Crane but also for some other globally threatened species, such as the Swan Goose (Anser cygnoides) and Great Bustard (Otis tarda). It is one of the key biodiversity nuclei in the Amur basin. But the ecosystems here face serious threats. The first threat consists of the frequent spring grassfires in the river valley. About 60%–70% of the wetlands, the breeding habitats for the birds, on the Russian part of the Argun valley burns every spring. According to my estimate about 30% of pairs of the Red-crowned Cranes annually lose clutches or cannot establish nests there because of this threat. On the Chinese territory of the Argun valley, grassfires are very rare.

Spring hunting and poaching in Russia form other threats. Cranes are not game species, but sometime they are shot illegally. Even the legal spring hunt creates intensive disturbance for breeding cranes.

The third threat is heavy water pollution from Chinese factories located along the Hailar River. Contaminants have a seriously debilitating effect on fish, an important food of the cranes. Concentration of contaminants increases considerably in dry years with less water in the river. Over-fishing by the Chinese people is an additional threat. Use of nets with small meshes to catch all fish including very young ones, combined with pollution of the water, have caused a sharp decline in fish in the river. In the past, the Argun had the richest fish resources in the Trans-Baikal Region, now it is one of the poorest rivers in the region.

The Argun region has very few underground water sources, therefore people living along the Hailar-Argun River and local industries depend very much on the water resources provided by the river. Fast urban growth coupled with water-thirsty industrial development form additional, large potential threats for the Argun wetlands. A major concern is the Hailar-Argun River water-diversion at Dalai Lake, a project which will divert at least 1 km3 (up to 1.5 km3) of water per year, 2/3 of the annual flow in a dry year. The project will have dramatic impact on wetlands along the lower reaches of the Argun River (Goroshko, 2007a; Simonov, et al., 2007).

The dynamics of the number of cranes in Dauria are closely connected with long-term climatic cycles and habitat dynamics. The shortage of water and wetland habitats is a major natural and anthropogenic limiting factor, connected with long-term climatic cycles and use of water by people. Its negative effect to crane populations is furthermore exacerbated by numerous anthropogenic factors (for example, because of grassfires, cranes cannot breed on some of the remaining drought stricken wetlands). As well, a lack of water in the river valley augments many anthropogenic threats: pollution, grassfires, disturbances. Therefore, dry climate periods are critical for population survival. To protect the valuable and vulnerable crane habitats and ecosystems in the Dauria Region, we Russian and Chinese people need to work together to deal with specific issues and find solutions. I propose to include the Argun valley in the Dauria International Protected Area or to create a new international Chinese-Russian nature reserve on the Argun.

The article is prepared with assistance from the Russian Fund for Basic Research, project 10-06-00060a and the World Wide Fund for Nature. I thank very much G.I. Fedurin, V.I. Fedotov and many other local people who have kindly provided me the data about cranes on the Argun. I am grateful to the staff of the Daursky Nature Reserve (especially – E.A. Simonov) for their support of my field observations and also to A.N. Barashkova and E.A. Vaseeva for their help in preparation of the article.

|

Gavrin GF, Rakov NV. 1959. Materials of study of spring migration of waterbirds on the upper flow of the Argun R. Part 1. USSR Science Academy Press, Moscow, pp 59–66. (in Russian)

|

|

Gavrin GF, Rakov NV. 1960. Materials of study of spring migration of waterbirds on the upper flow of the Argun R. Part 2. USSR Science Academy Press, Moscow, pp 146–174. (in Russian)

|

|

Golovushkin MI, Goroshko OA. 1995. Cranes and storks in South-Eastern Transbaikalia. In: Halvorson CH, Harris JT, Smirenski SM (eds) Cranes and Storks of the Amur River, The Proceedings of the International Workshop. Art Literature Publishers, Moscow, p 39.

|

|

Goroshko OA. 2002. Status and conservation of populations of cranes and bustards in South-Eastern Transbaikalia and North-Eastern Mongolia. Dissertation. All-Russian Institute for Nature Protection, Moscow, Russia, p 194. (in Russian)

|

|

Goroshko OA. 2007a. Global ornithological importance of upper part of the Argun R. and problems of its conservation. In: Konstantinov MV (ed) Cooperation in Conservation of Nature between Chita Region (the Russian Federation) and Inner Mongolia (People's Republic of China) in Transboundary Ecological Regions. Proceedings of International Conference. Zabaikalsky State Humanitarian Pedagogical University Press, Chita, pp 80–90. (in Russian)

|

|

Goroshko OA. 2007b. The Chinese-Russian Argun River is a threatened globally important site of cranes, geese, swans and other birds. China Crane News, 11(2): 28–34.

|

|

Goroshko OA, Tseveenmyadag N, Liu ST, Li M, Bai YS. 2002. Red-crowned Cranes in Dauria steppes. Newsletter of Crane Working Group of Eurasia, 4–5: 41.

|

|

Obiazov VA. 1994. The relationship of the water level fluctuations in lakes of Transbaikalian steppe zone to hydrometeorological changes during many years on an example of the Torey Lakes. News of the Russian Geographical Society, 5: 48–54. (in Russian)

|

|

Pallas PS. 1788. The journey through miscellaneous provinces of Russian state. Part 3. Half 1. St. -Peterburg. (in Russian)

|

|

Radde G. 1863. Reisen im Süden von Ostsibirien in den Jahren 1855–1859. Bd. 11. Die Festland-Ornis des Sudostlichen Sibiriens. St. -Petersburg. (in German)

|

|

Shulpin LM. 1936. Game-birds and birds of prey of Primorye. Vladivostok, p 436. (in Russian)

|

|

Simonov EA, Goroshko OA, Luo ZH, Zheng LJ, Chen L. 2007. Wetlands of Argun midflow — to be or not to be? Preliminary overview of development patterns and environmental impacts. In: Konstantinov MV (ed) Cooperation in Conservation of Nature between Chita Region (the Russian Federation) and Inner Mongolia (People's Republic of China) in Transboundary Ecological Regions. Proceedings of International Conference, Zabaikalsky State Humanitarian Pedagogical University Press, Chita, pp 278–286.

|

|

Stegmann B. 1929. Die Vögel Sud-Ost Transbaikaliens. Year-book of Zoological Mus. of Academy of Science (1928), 29: 83–242. (in German)

|

|

Taczanowski L. 1893. Faune ornithologique de la Sibérie Orientale. Mémoires de l'Académie Impériale des sciences de St. -Pétersbourg, sér. 7, t. 39. St. -Pétersbourg.

|